J. Paul Getty Museum

17 / 42 The Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90049

The J. Paul Getty Museum, with locations in Malibu (Getty Villa) and Los Angeles (Getty Center), caters to diverse audiences with a wide range of art exhibitions and programs in visual arts.

The Getty Center features works of art dating from the eighth through the twenty-first century, showcased against a backdrop of dramatic architecture, tranquil gardens, and panoramic views of Los Angeles. The collection includes European paintings, drawings, sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, decorative arts, and European, Asian, and American photographs.

The Getty Villa in Malibu features Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities presented in a setting modeled after a first-century Roman country house, the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum, Italy.

Spanish collection

The following 34 Spanish artworks are a selection from the museum's collection.

Leaf from Commentarius in Apocalypsim

by Saint Beatus of Liébana, circa 1220–1235

- Medium

- Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink

- Dimensions

- Leaf: 29.4 × 23.5 cm (11 9/16 × 9 1/4 in)

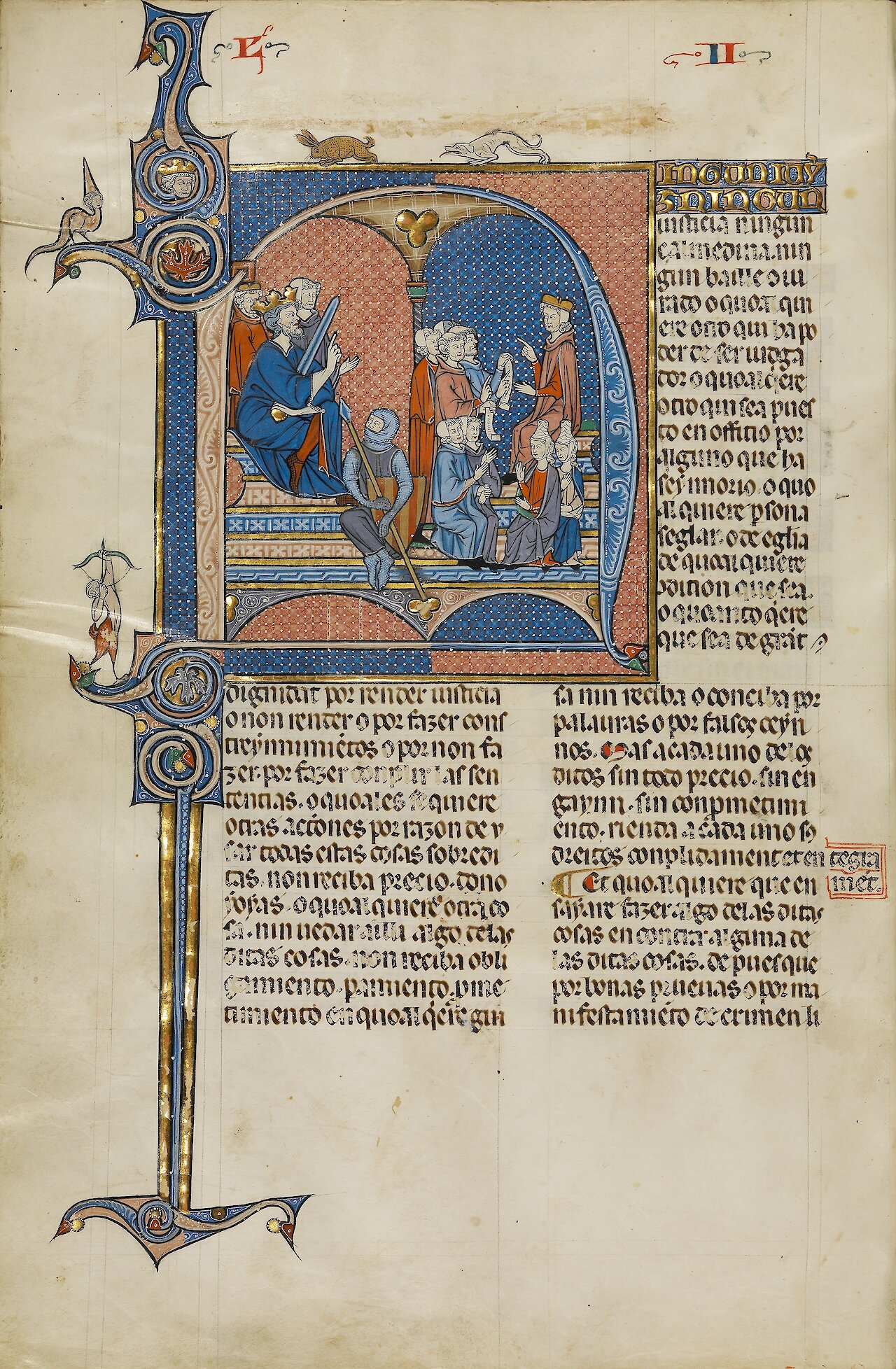

Vidal Mayor

by Anonymous / Unknown, circa 1290–1310

- Medium

- Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink

- Dimensions

- Leaf: 36.5 × 24 cm (14 3/8 × 9 7/16 in)

- Notes

By unknown artist/maker, Vidal de Canellas (Spanish, active Aragon, Spain 1236-1252), and probably Michael Lupi de Çandiu (Spanish, active Pamplona, Spain 1297-1305).

In 1247, with the reconquest of Spain from the Muslim forces virtually complete, King James I of Aragon and Catalonia, Spain, decided to establish a new systematic code of law for his kingdom. He entrusted the task to Vidal de Canellas, bishop of Huesca. The Getty Museum's manuscript, the only known copy of the law code still in existence, is a translation of Vidal de Canellas's Latin text into the vernacular Navarro-Aragonese language (in that language, the book is called Vidal Mayor in reference to the author). The manuscript's scribe was Michael Lupi de Çandiu, who identifies himself in an inscription and who also may have translated the text.

Not only is the text an important historical document but it is luxuriously illuminated with hundreds of historiated and decorated initials. Although written and illuminated between 1290 and 1310 in one of the major urban centers in northeastern Spain, the elegant style of the painting reveals an intimate link with contemporary French illumination. This stylistic connection demonstrates the increased movement of both artists and manuscripts from one European court to another.

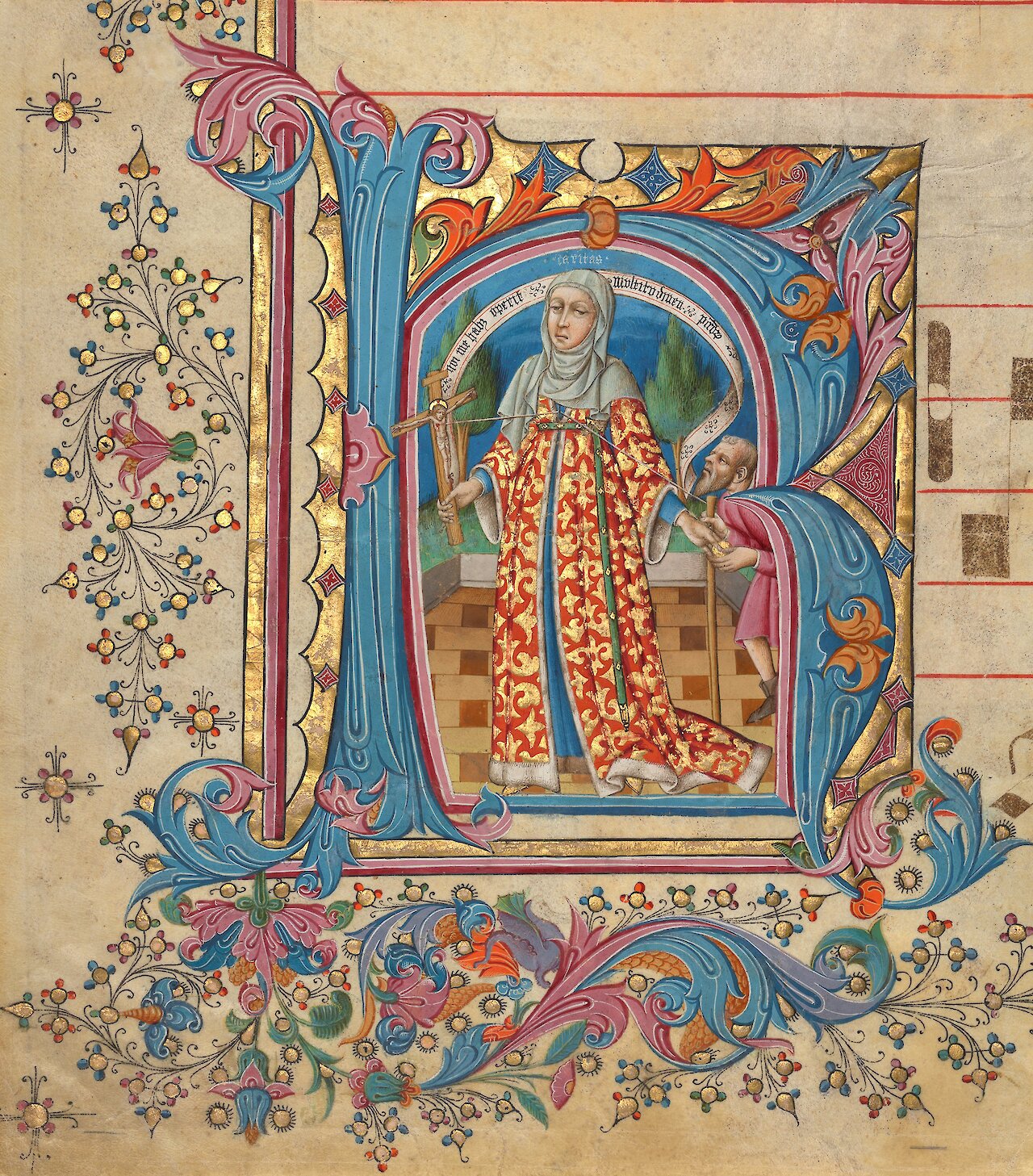

Historiated Initial from a Gradual

by Master of the Cypresses, circa 1430–1440

- Medium

- Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink

- Dimensions

- Leaf: 36 × 31.5 cm (14 3/16 × 12 3/8 in)

- Notes

At the core of this manuscript leaf is an ornate decorative initial, a lavish letter "K" that serves as a visual ode to the virtue of Caritas, or love. The illustration depicts Charity as a richly attired woman, symbolizing the divine nature of God's love. The initial is intricately adorned with elaborate patterns and flourishes, a hallmark of the style associated with the Master of the Cypresses (active in the 1430s), an artist renowned for ornate design.

Believed to be the work of Pedro de Toledo (active in 1434), who was documented as an artist at Seville Cathedral during the 1430s, de Toledo was bestowed the title of "Master" by art historian Diego Angulo Íñiguez (1901–1986) in 1428.

Set against a deep blue backdrop, the letter "K" gleams resplendently in gold, with its intricate curves and lines meticulously rendered. Within the letter, two figures locked in an intimate embrace symbolize profound love and unwavering devotion. Caritas, or Charity, holding a crucifix in her right hand, tenderly extends a singular gold coin to the beggar before her. The intersecting geometric lines elegantly connect three essential elements of the Trinity: Charity's heart, the beggar's staff, and Christ's wound, symbolizing divine salvation through God's boundless charity.

Pietà

by Fernando Gallego, circa 1490–1500

- Medium

- Oil on panel

- Dimensions

- Unframed: 49.8 × 34.3 cm (19 5/8 × 13 1/2 in); framed: 55.9 × 40.6 × 5.1 cm (22 × 16 × 2 in)

- Notes

By the circle of Fernando Gallego.

In this depiction of the lamentation of Christ, Fernando Gallego looked to Northern European paintings for inspiration but included distinctly Spanish elements such as a subdued palette and unidealized figures. Unlike Netherlandish artists who were interested in depicting the natural world in minute detail, Gallego concentrated on the pietà's psychological and emotional impact, eliminating extraneous or distracting elements.

The Virgin Mary sits in front of the cross, gazing at her dead son in her lap. On the ground around them are several pebbles, a bone, and a skull. A lance and a rod with attached sponge, two instruments from the Passion, lean perfectly vertically against the cross, which is inscribed with the initials i.n.r.i. Behind the cross a rocky landscape overlooks a Gothic walled town, settled between a body of water and verdant countryside that stretches into the far distance.

Gallego focused on the moment after the Crucifixion when overwhelming anguish gave way to resigned misery, the sentiment evident in the grief-stricken face of the Virgin, flushed and swollen from weeping. Christ's broken and emaciated body, his eyes unseeing, stretches awkwardly across her lap. Their exaggerated and unidealized features intensify the pathos central to the theme of the pietà.

Christ Carrying the Cross

by Juan de Juanes, circa 1560

- Medium

- Pen and brown ink and brown wash over black chalk; the upper left and right corners trimmed diagonally and made up

- Dimensions

- 21 × 34.8 cm (8 1/4 × 13 11/16 in.)

- Notes

Juan de Juanes actively worked out his ideas in this drawing, first in black chalk lines, which are faintly visible under the bolder pen-and-ink forms. In the earlier chalk rendition, he drew the figure of Christ farther to the left, carrying the cross with his right arm. The soldier to the right, leading him by the rope about his neck, was also father to the left, while two additional soldiers, faintly drawn in the top right, were not developed in pen. The Holy Women kneeling before him also changed when Juanes finished the drawing in pen after making the chalk underdrawing. He used the brown ink to model the forms in three dimensions with extensive, insistent hatching and cross-hatching. The artist's technique and the spatial clarity of the individual figures reflect the influence of Raphael, whose paintings he studied on a visit to Italy around 1560.

The Coronation of the Virgin

by Francisco Ribalta, circa 1600–1628

- Medium

- Pen and brown ink and brown wash

- Dimensions

- 28.7 × 18.7 cm (11 5/16 × 7 3/8 in)

- Notes

Tumbling angels support the Virgin Mary as she graciously accepts the crown as Queen of Heaven. During the mid-1660s, the Coronation of the Virgin was a very popular subject in Catholic circles, especially in Spain. Francisco Ribalta treated the theme with remarkable dynamism and originality. He applied wash to strengthen the vigorous pen work and to unite the composition. The arched upper section suggests that he made the drawing in preparation for an altar painting.

St. Jerome Hearing the Trumpet of the Last Judgment

by Vicente Carducho, circa 1626–1632

- Medium

- Black chalk with brown wash, heightened with white gouache, squared in black chalk

- Dimensions

- 31.8 × 21.6 cm (12 1/2 × 8 1/2 in)

- Notes

With a long beard and curling locks, a slightly disheveled Saint Jerome listens open-mouthed in astonishment as an angel overhead sounds its trumpet. Vicente Carducho drew Jerome interrupted in the act of writing, with his faithful friend and attribute the lion by his side.

Artists often showed Jerome writing, undoubtedly a common activity for the learned saint who translated the Bible into Latin. Jerome commonly appeared nearly nude, giving artists the opportunity to display his gaunt, ascetic figure. Carducho suggested the saint's lean, muscular body with brown wash and white gouache, using while radiating strokes of black chalk to describe the drapery, which nearly merges with the rocks. The artist reworked the saint's right leg several times, positioning it first forward and then further back until it rested underneath his left knee. The black chalk squaring on this drawing implies that Carducho intended this drawing as a preparatory study for a large painting, although scholars have not identified such a work.

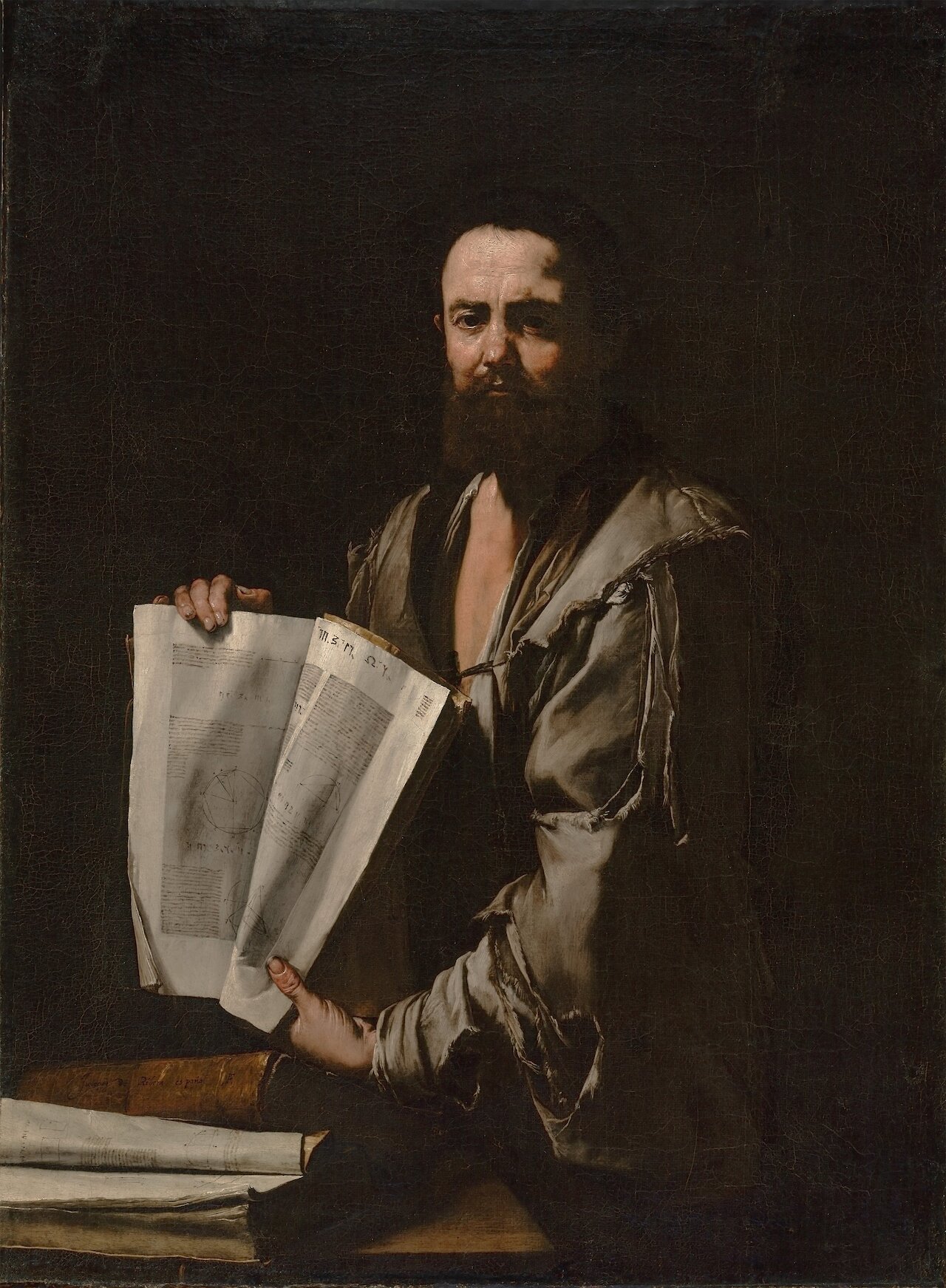

Euclid

by Jusepe de Ribera, circa 1630–1635

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- Unframed: 125.1 × 92.4 cm (49 1/4 × 36 3/8 in); framed: 158.1 × 124.5 × 7.3 cm (62 1/4 × 49 × 2 7/8 in)

- Notes

Emerging from deep shadows behind a table, a solemn individual stands displaying a well-worn book with various geometric figures, pseudo-Greek characters, and an imaginary script. Jusepe de Ribera paid considerable attention to the man's facial details, from the unkempt beard to the distinctive creases of his high forehead and the irregular folds of the lids above his dark, penetrating eyes. He depicted the wise man with tattered clothes and blackened, grimy fingers to emphasize the subject's devotion to intellectual, rather than material, pursuits.

The presence of mathematical diagrams in the illegible book reveal the figure's identity as Euclid, a prominent mathematician from antiquity, best known for his treatise on geometry, the Elements. Portraits of wise men were very popular in the 1600s, when there was a revived interest in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy. Rather than portraying the subject as a refined and noble figure, Ribera depicted him as an indiv

St. Jerome Hearing the Trumpet of the Last Judgment

by Antonio del Castillo y Saavedra, circa 1645–1650

- Medium

- Reed pen and brown ink, heightened with white gouache

- Dimensions

- 29.4 × 19.8 cm (11 9/16 × 7 13/16 in)

- Notes

Living in the wilderness as a hermit, Saint Jerome heard trumpets sounding the Last Judgment; looking up, he saw the cross with Christ's body rising in front of him. Here the trumpet appears so tantalizingly close that Jerome reaches up to try to touch it. His attributes, a lion and a book, surround him.

Antonio del Castillo y Saavedra built the dynamic composition from lively, quick strokes. Hatching and cross-hatching emphasize the rippling muscles on the saint's arms and back and elaborate the folds of fabric around his waist. They suggest the undergrowth on the left and the lion's fur.

The Assumption of the Virgin

by Francisco de Herrera el Mozo, circa 1648–1653

- Medium

- Pen and brown ink, brown wash over black chalk

- Dimensions

- 30.6 × 21.7 cm (12 1/16 × 8 9/16 in)

- Notes

Through lively penwork, de Herrera imparted a sense of movement to the substantial figure of the Virgin and the stable, classical pyramid form of the group. The artist's fertile imagination worked quickly; after doing some sketching with black chalk, he applied free-flowing, crisscrossing, tangled threads of ink ranging from the dark squiggles of the Virgin's drapery to the light tracings on the angels' robes below. The fluent washes add drama to the composition.

The Visitation

by Juan Carreño de Miranda, circa 1655–1660

- Medium

- Pen and brown ink and gray-brown wash, heightened with white gouache, over touches of black chalk (recto); black chalk (verso)

- Dimensions

- 24.8 × 23.7 cm (9 3/4 × 9 5/16 in)

- Notes

Two cousins share in a moment of mutual happiness in this scene of rejoicing. The Virgin Mary rushes up the steps to congratulate her elderly cousin Saint Elizabeth, placing her left hand on Elizabeth's shoulder and clasping the other. Both women celebrate their respective pregnancies, the Virgin with the infant Jesus and Elizabeth with John the Baptist. Elizabeth had particular cause for celebration as she had conceived in old age, after a lifetime of barrenness.

Juan Carreño de Miranda conveyed the scene thorough energetic motion and nervous handling of the pen. Vigorous strokes describe the flowing outline of the Virgin's cloak, while summary passages of wash in gray-brown define Elizabeth's head and back. Amid the swirling mass of lines on the left several indistinct heads are visible. Another mother crouches at the foot of the steps, holding a baby in her arms.

Equestrian Portrait of Don Juan José of Austria

by José Ximénez Donoso, circa 1660–1680

- Medium

- Brown ink and brown wash over black chalk, heightened with white gouache, squared in black chalk (recto); black chalk (verso)

- Dimensions

- 23.2 × 21.3 cm (9 1/8 × 8 3/8 in)

- Notes

A highly successful and ruthless general, Don Juan José of Austria suppressed an anti-Spanish uprising in Naples when he was only eighteen years old. This scene shows his triumphal entry following the suppression of the revolt. A young fisherman had led a protest against a new tax on fruit imposed by the aristocracy; the protest later turned into an insurrection aiming at slaughtering the nobility. As the general leads his cavalry into the city, trampling a child underfoot, he receives the homage of the population in the person of the bearded man kneeling to the left, who offers a platter containing three utensils, perhaps representing the keys of the city.

José Ximénez Donoso copied the equestrian figure from a well-known etching by Jusepe de Ribera but added soldiers and spectators to the background. The artist drew the whole scene in black chalk but reinforced the forms of Don José and his horse, copied from the print, in pen and brown ink. The drawing is squared for transfer, implying that the composition was intended for a painting or perhaps a print.

The Vision of Saint Francis of Paola

by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, circa 1670

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- Unframed: 188 × 146 cm (74 × 57 1/2 in); framed: 220.3 × 177.8 × 15.9 cm (86 3/4 × 70 × 6 1/4 in)

- Notes

This painting depicts the heavenly vision of Saint Francis of Paola (1416–1507), founder of the Order of Minims, a religious order committed to perpetual abstinence and acts of humility. The saint experiences a vision in which the word “Charitas” (meaning Charity) appears in an aureole of golden light, accompanied by cherubs. The word became the motto of the Minims, and appears on the order’s heraldic crest.

In the background, the saint appears again standing on a shore with two kneeling companions. This scene in the distance refers to a miracle in which Francis calmed a stormy sea and ferried the men across the Straits of Messina on his cloak after they had been refused passage on a ship.

The subject of the painting should not be considered simply in terms of its visionary and narrative elements, but as a representation of faith itself as embodied by Saint Francis of Paola. Elderly and bearded, he is humbly dressed and appears to bear the weight of his calling on his slender walking staff. He gazes at the message borne aloft by the heavenly host with a look of reverent awe and dutiful acceptance. The simplicity of setting, sober tonality, loose brushwork, and harmony of both material and divine presence, are all consistent with Murillo's late style and help to convey a scene of passionate spiritual appeal.

Study for a Statue of Queen Isabella

by Pedro de Mena, 1673–1673

- Medium

- Black chalk, pen and brown-gray ink, with yellow, gray and red wash

- Dimensions

- 34.4 × 23.3 cm (13 9/16 × 9 3/16 in)

- Notes

Before an altar with a crown on a large cushion, Queen Isabella the Catholic kneels in silent prayer. She kneels atop an ornate bracket with an empty escutcheon and a large crown in the center, flanked by various emblems and trophies including pomegranates, flags, suits of armor, and two nude men.

The study gives enough careful detail to allow a stone carver to accurately reproduce this proposed design for a polychrome marble statue of the Spanish queen. The calibrations, numbered one to six along the right side of the sheet, would have allowed another craftsman to judge the scale of the work. The careful shading down the right edge of the bracket and around the emblems that hang from it suggests that these areas should project further forward than the top portion of the design. The rectangular frame around the queen represents a shallow niche.

Pedro de Mena y Medrano produced the design for a statue for the main chapel of the cathedral of Granada. A pendant statue portrays Isabella's husband, Ferdinand II of Aragon, who kneels opposite her. So popular were the two statues that they were copied for another cathedral, in Málaga.

Study for a Ceiling with the Virgin and Christ in Glory

by Francisco Rizi, circa 1678

- Medium

- Pen and brown ink and brown wash with some graphite

- Dimensions

- 26.7 × 28.9 cm (10 1/2 × 11 3/8 in)

- Notes

Francisco Rizi made this complete decorative and architectural design for a cupola, a small dome of a church. The central compartment depicts the Virgin Mary and Christ seated amid clouds and framed on four sides by pairs of putti supporting balustrades. In the lower right corner, Rizi drew a prophet. Rizi was Madrid's major practitioner of illusionistic architectural painting, or quadratura, which Italian artists had introduced earlier in the 1600s. The building for which this design was intended is not known.

The Exaltation of the Cross

by Juan de Valdés Leal, circa 1680

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- Unframed: 62.9 × 107.6 cm (24 3/4 × 42 3/8 in); framed (approx.): 78.1 × 112.1 × 5.7 × 9.5 cm (30 3/4 × 44 1/8 × 2 1/4 × 3 3/4 in)

- Credits

- Anonymous gift in honor of Scott Schaefer

- Notes

Surrounded by a diverse array of onlookers, the Byzantine emperor Heraclius kneels and prepares to raise the holy cross. Barefoot and clad in drab robes, Heraclius has abandoned his fine clothing in order to pass through the gate of Jerusalem with humility. Standing beside Heraclius and clad in a bishop's mitre and white robe is the patriarch of Constantinople, Zachariah. Around this central pair, several spectators have dropped to their knees at the sight of the cross. In 628 A.D., having recovered the true cross from the Persians, Heraclius appeared at the gate of Jerusalem intending to enter in triumph. But as he and his followers approached the gate, stones fell from the walls, blocking his passage. An angel appeared and told him that in his opulent clothes, he could not enter through the same gate that Christ had humbly entered riding on a donkey. The message of this story is clear: the kingdom of heaven is open only to those who have forsaken the riches of the material world. The Exaltation of the Cross, in the form of a narrative series, appeared in several early Renaissance frescoes. But it is a subject rarely represented in painting. Juan de Valdés Leal frequently used painted sketches to work out his ideas for large-scale compositions. This oil sketch was created for his last major commission, a monumental fresco for the church of the Hospital de la Caridad in Seville, Spain. This preparatory sketch highlights Valdés Leal's agitated brushwork, thick impasto, vivid coloring, and dramatic sense of movement. Such painterly spontaneity perhaps reflects the spiritual fervor of this famously volatile painter.

Saint Ginés de la Jara

by Luisa Roldán (La Roldana), circa 1692

- Medium

- Polychromed wood (pine and cedar) with glass eyes

- Dimensions

- Object: H: 175.9 × W: 92 × D: 74 cm (5 ft 9 1/4 in × 3 ft. 3/16 in. × 2 ft 5 1/8 in)

- Notes

In a richly brocaded robe, with rosy cheeks, shining eyes, and outstretched arms, Saint Ginés de la Jara appeals to the faithful standing before him. His gestures and open mouth suggest that he is preaching. According to legend, after Saint Ginés was decapitated in southern France, he picked up his head and tossed it into the Rhône River. Carried by the sea to the coast of southeastern Spain, it was retrieved and conserved as a relic. Life-sized, devotional cult objects often included glass eyes and were often made out of wood that could be painted in order to achieve lifelike results. Reinforcing the emotional experience of the faithful, such heightened realism typified Spanish Baroque art at a time when the Catholic Church sought to make Christianity more accessible to believers.

Luisa Roldán, also called La Roldana, carved the work. The figure was polychromed by her brother-in-law, Tomás de los Arcos, who used the Spanish technique of estofado to replicate the brocaded ecclesiastical garments. In this process, the area of the figure's garment was first covered in gold leaf and painted over with brown paint, and then incised with a stylus to reveal the gold underneath.

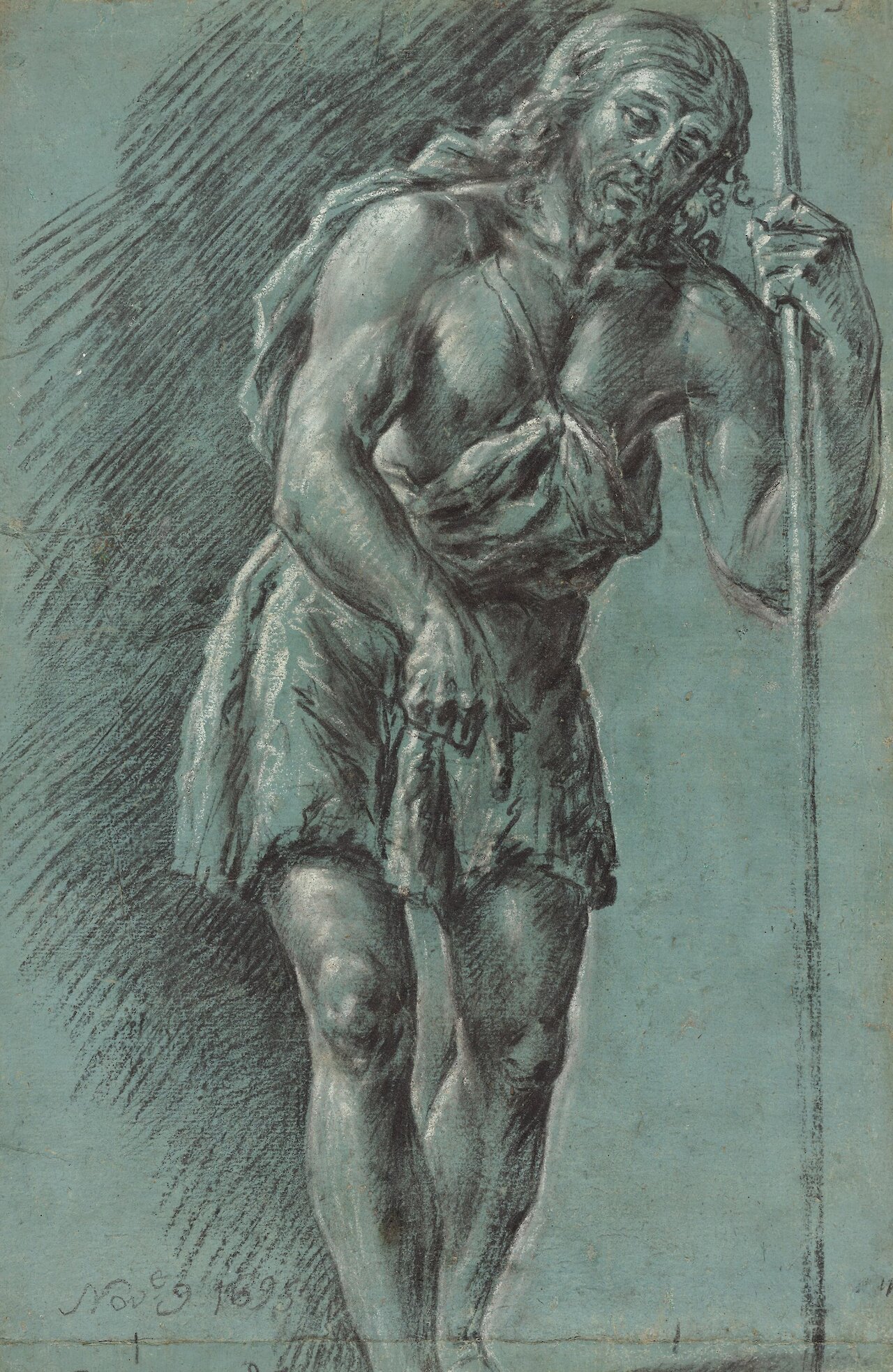

Saint John the Baptist

by Anonymous / Unknown, circa 1740

- Medium

- Charcoal, heightened with opaque white watercolor

- Dimensions

- 43 × 26.9 cm (16 15/16 × 10 9/16 in)

- Credits

- Purchased with funds provided by the Disegno Group.

- Notes

After Juan Conchillos Falcó (Spanish, 1641-1711). On striking blue prepared paper, this academic figure study is posed as Saint John the Baptist. Seen from below, suggesting that the model stood on a raised platform, the saint looms large. The artist modeled his figure using the blue as a middle tone. Charcoal and white watercolor forcefully articulate the anatomical form of the saint, and convey his powerful presence. The saint's musculature is dramatically portrayed in gritty black lines built up in bold succession. The summary treatment of the drapery, executed in broad, jagged strokes, gives the saint's clothing an abstract quality that reiterates the drawing's primary purpose as a study of the male body. On close examination, the charcoal's rough texture reflects glints of light, creating a seamless marriage between medium, technique, and subject.

Plaque depicting Jacob choosing Rachel to be his Bride

by Alcora Ceramic Factory, circa 1755

- Medium

- Faïence (tin-glazed earthenware)

- Dimensions

- Object (height x width): 94 × 47.6 cm (37 × 18 3/4 in)

- Notes

Clad in complementary yellow and blue, a young man and woman coyly eye each other, their hands meeting at the very center of the scene. Lively, overflowing foliage serves as a dramatic and fitting backdrop to this courtship. At the base of the plaque, an inscription in Latin that identifies the pair translates as: Behold the very beautiful Rachel with her sheep, whom Jacob chooses as his wife.

After painting by Jacopo Amigoni (Italian, 1682-1752). Despite the inscription, the scene also includes several details from the biblical account of Rebecca and Eliezer at the well. The jar balanced on the well, the flamingolike camels in the background, and the jewel-laden chest in the foreground are elements of this story. The plaque is based on a mid-seventeenth century image of Rebecca and Eliezer by Jacopo Amigoni, whose paintings and engravings often served as a model for the decoration of plaques and tapestries. It is likely that the painter of the plaque had a print of Amigoni's work in hand but transformed it into the more amorous Jacob and Rachel subject, probably for a specific patron.

The Virgin Annunciate (recto); Sketch of a Figure (verso)

by Francisco Bayeu y Subias, circa 1769

- Medium

- Black chalk with touches of white (recto); black chalk (verso)

- Dimensions

- 47 × 31.5 cm (18 1/2 × 12 3/8 in)

The Apparition of the Virgin and Child to Saint Louis of France

by Mariano Salvador Maella, circa 1780–1790

- Medium

- Pen and brown ink and brown wash over black chalk; squared in black chalk

- Dimensions

- 21 × 14.4 cm (8 1/4 × 5 11/16 in)

- Notes

Saint Fernando gazes upward, paying homage to a vision of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child floating on a pillow of clouds surrounded by winged putti. The arched top and the squaring suggest that the artist planned a painted altarpiece.

The quick, loose strokes merely outlining the figures and the broadly applied wash alluding to their volume indicate that this preliminary drawing was made to work out the placement of the various characters. While the artist focused on the poses and gestures of the Virgin, Child, and saint, he ignored other, more intricate details. He simply suggested Jesus' features with a small dot for his eye and a single line indicating hair. Simple circles and arched lines suggest the heads and wings of the putti.

Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene

by Vicente López y Portaña, 1795–1800

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- Unframed: 78.7 × 64.5 cm (31 × 25 3/8 in); framed: 91.4 × 63.8 × 4.8 cm (36 × 25 1/8 × 1 7/8 in)

- Credits

- Gift of Stanley Moss in honor of John Walsh

- Notes

This painting illustrates the Roman widow Irene nursing Saint Sebastian back to health after he was discovered to be a Christian and shot with arrows by Roman archers. Writhing in pain, Saint Sebastian looks heavenward as Saint Irene pulls arrows from his pierced body. Vicente López y Portaña dynamically composed the figure of Sebastian, with one arm tied above his head and his other arm held by an attendant, in order to more clearly display the wounds on his upper body and to allude to the martyrdom of Christ. Sebastian's bent leg reveals the bleeding gash from which Irene has already removed one arrow. As she leans toward Sebastian's knee, she carefully pulls the saint's flesh in order to extract a second arrow. In the foreground, the depiction of the armor and weapons Sebastian wore as a military captain signals that this event occurred in ancient Rome.

López y Portaña's luscious palette and creamy application of paint contrast with the drama and emotion of this religious story. Like Andrea Lilio's Figures Tending to the Wounded Saint Sebastian, this painting differs from representations that show the Saint bound to a tree or pillar, moments after the attack.

Portrait of the Marquesa de Santiago

by Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, 1804

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- Unframed: 209.9 × 126.7 cm (82 5/8 × 49 7/8 in.) Framed: 235.3 × 150.2 × 9.5 cm (92 5/8 × 59 1/8 × 3 3/4 in)

- Notes

The Marquesa de Santiago strikes a commanding presence, confronting the viewer directly with her hand assertively on her hip. She stands in front of a landscape of gently sloping hills dotted with cottages made up of rough, tan brushstrokes. Her sheer white lace mantilla veil extends to her knees and she holds a closed fan in her left hand, both traditional accessories of Spanish women in the 1700s and 1800s. The Marquesa was known to wear bold makeup, enough that her acquaintances wrote about it, and here, heavily applied rouge, powder, and lipstick accentuate her features. While other portraitists of this time often flattered or idealized their sitters, Francisco Goya frankly captured the Marquesa’s appearance and confident personality.

The Marquesa, María de la Soledad Rodríguez de los Ríos Tauche, grew up the only child of a well-connected family in Madrid, eventually inheriting the three noble titles of her parents and the wealth that came with those. Married first in 1783 when she was eighteen, then again in 1790 after she was widowed, María was the one who brought greater wealth and status to her husbands. She had estates in Flanders and Spain, two million reales in capital (the Spanish currency used from the 1300s to 1860s), and two million more in silver, jewelry, and other possessions. This portrait, though painted as a pair to her second husband’s, unconventionally touts her own title, Santiago, in the inscription in the lower right, rather than his, San Adrían, which would have been typical for her to adopt as his wife. As the more elite of the couple, she may have decided to commission these portraits from Goya to add to her family’s substantial paintings collection.

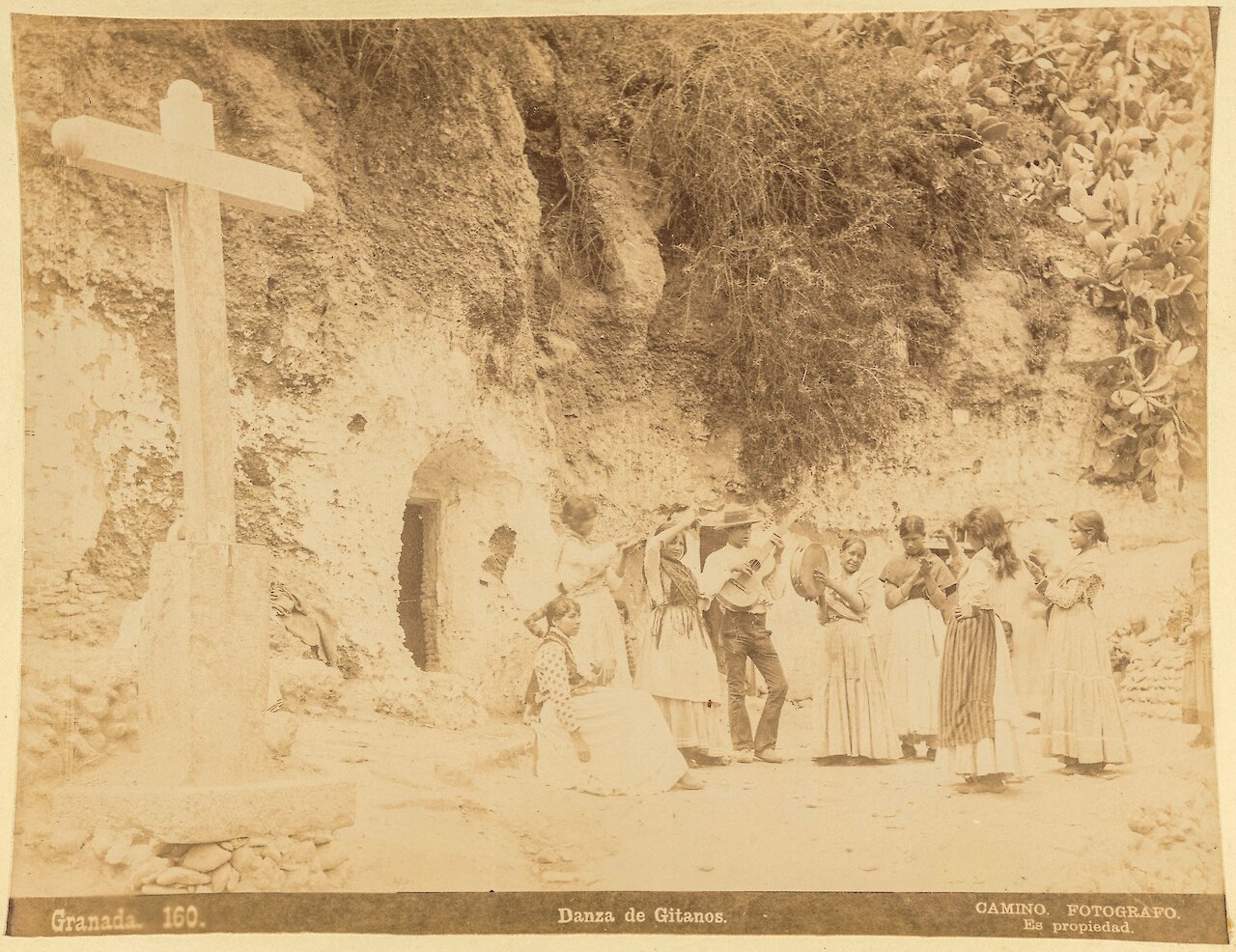

Danza de Gitanos

by José Camino Vaca, 1850–1888

- Medium

- Albumen silver print

- Dimensions

- Image: 20.5 × 26.2 cm (8 1/16 × 10 5/16 in); mount: 25.4 × 31.5 cm (10 × 12 3/8 in)

- Notes

A man playing guitar in a circle with a group of women who are dancing or playing tambourines. The group is next to a large wooden cross at the base of a mountain.

Sevilla. Del patio de la Casa de Pilatos

by Alejandro Massari, circa 1857

- Medium

- Albumen silver print

- Dimensions

- Image: 20.5 × 15.7 cm (8 1/16 × 6 3/16 in); mount: 41.8 × 32.4 cm (16 7/16 × 12 3/4 in)

- Notes

Interior courtyard with a statue of a figure holding a spear and shield on a pedestal. The courtyard has rows of arches and an ornately designed balcony on the second level.

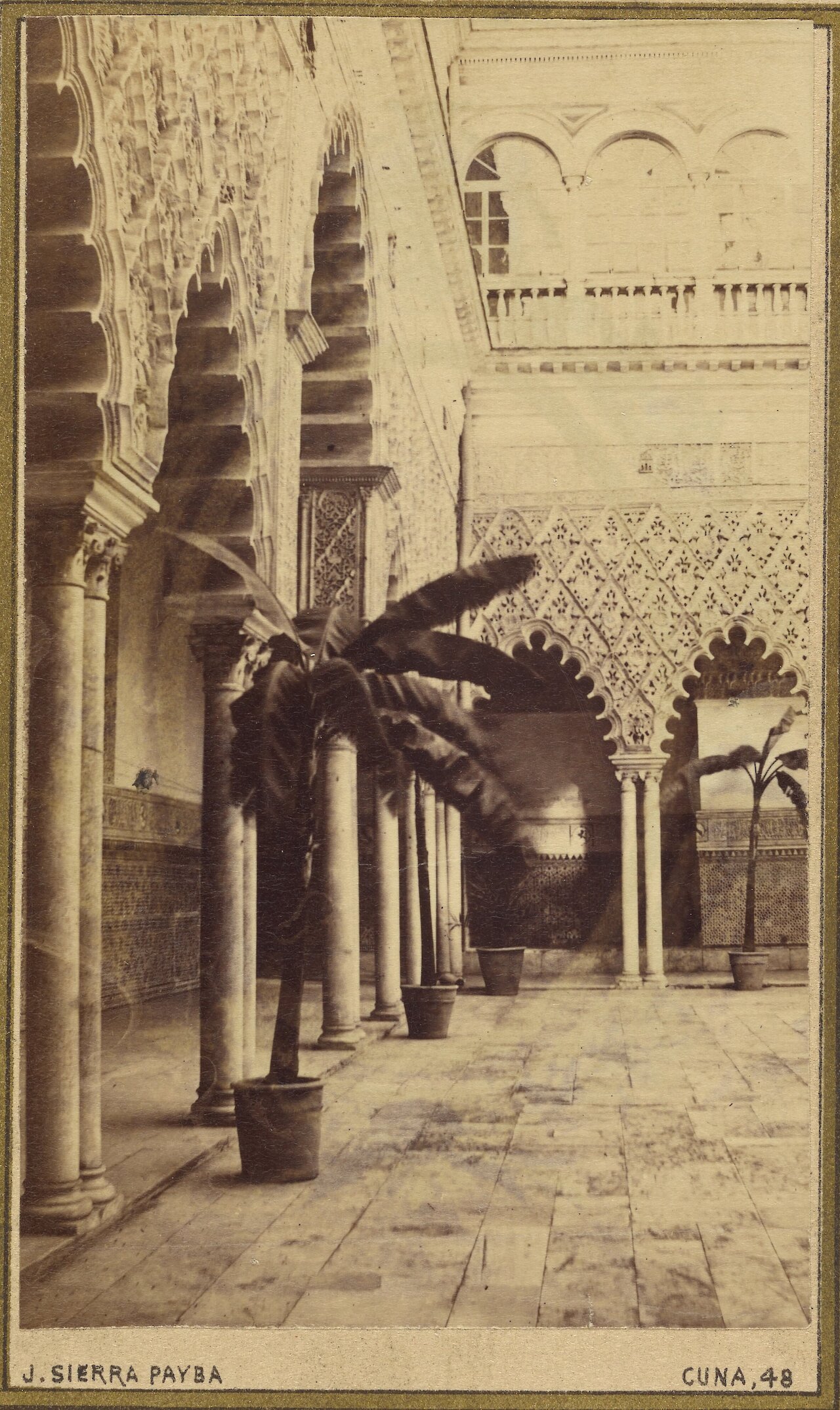

Sevilla, Casa de Pilatos Patio

by Luis Leon Masson, circa 1860–1870

- Medium

- Albumen silver print

- Notes

Gift of Weston J. and Mary M. Naef

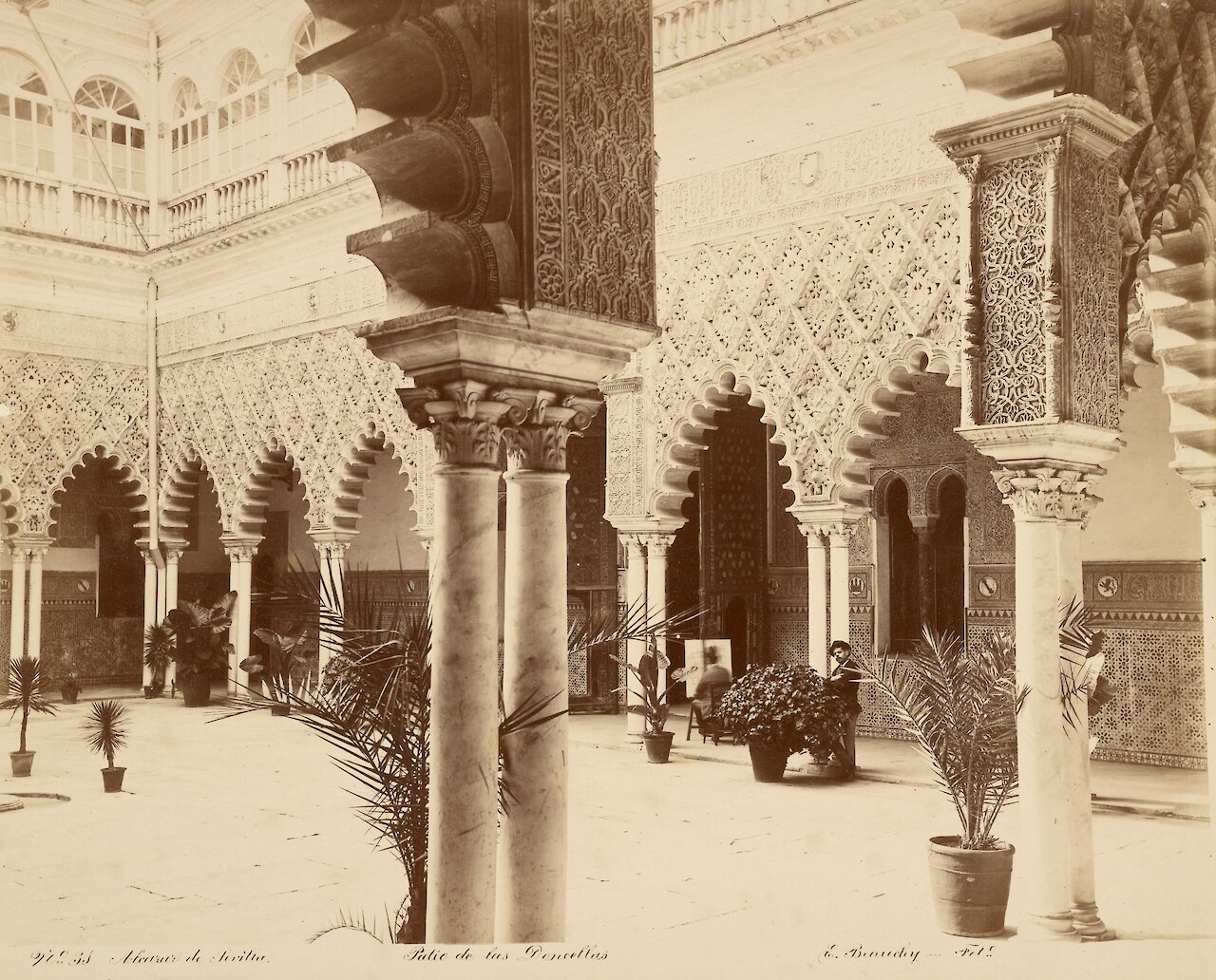

Court of the Maidens, Alcazar, Seville, (Patio de las Doncellas, Alcazar, Sevilla)

by Emilio Beauchy, 1870

- Medium

- Albumen silver print

- Dimensions

- Image: 24 × 29.5 cm (9 7/16 × 11 5/8 in)

Cordoba, Detalle interior de la Mezquita

by J. E. Puig, circa 1875

- Medium

- Albumen silver print

- Dimensions

- Image: 16.5 × 22.1 cm (6 1/2 × 8 11/16 in); mount: 25.8 × 30.4 cm (10 3/16 × 11 15/16 in)

- Notes

Interior hall of the Mosque of Cordoba with multiple rows of columns and arches. The arches have a striped pattern.

Detalles de San Juan de los Reyes, Toledo

by Casiano Alguacil, 1875

- Medium

- Albumen silver print

- Dimensions

- Image: 19.4 × 40.5 cm (7 5/8 × 15 15/16 in); mount: 44.1 × 34.9 cm (17 3/8 × 13 3/4 in)

- Notes

Three religious statues resting on niches on a pillar.

Nuns at Mass

by Amedor, 1900

- Medium

- Gelatin silver print

- Dimensions

- Image: 16.4 × 22.7 cm (6 7/16 × 8 15/16 in)

- Notes

The inside of a cathedral during mass. Nuns sit in rows wearing white cornette hats, facing towards the altar where priests and bishops kneel on the ground. Lit candles cover the altar.

Pepilla and her Daughter

by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, 1910

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- Unframed: 181.6 × 110.5 cm (71 1/2 × 43 1/2 in); framed (Display): 200.7 × 129.5 × 10.2 × 8.3 cm (79 × 51 × 4 × 3 1/4 in)

- Notes

Handsome and proud, Pepilla sits with one arm around her daughter's shoulders and her other hand on her hip. Both mother and daughter gaze directly out at the viewer. Just as the mother's gesture tenderly protects yet presents her daughter, Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida expressed tenderness in his portraits of Spanish people, particularly women and children.

With his typical spontaneous, broad brushwork, Sorolla reveled in the effects of the warm Mediterranean light and air on the colors and patterns in the women's costumes. He preferred to paint even portraits outdoors, trying to achieve a spontaneous effect. "[N]o matter how much labor you may have expended on the canvas, the result should look as if it had all been done with ease and at a sitting," he said in 1909.